COMING SOON

A recording that explores the thin boundaries between EVP, the cut-up technique, and tragedy. Featuring William Burroughs and EVP recordings captured at Burroughs’s gravesite.

Death is the permanent, irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. Death is an inevitable, universal process that eventually occurs in all organisms. One of the challenges in defining death is in distinguishing it from life. As a point in time, death would seem to refer to the moment at which life ends.

It is possible to define life in terms of consciousness. When consciousness ceases, an organism can be said to have died. Historically, attempts to define the exact moment of a human’s death have been subjective, or imprecise. Today, doctors usually turn to “brain death” or “biological death” to define a person as being dead; people are considered dead when the electrical activity in their brain ceases.

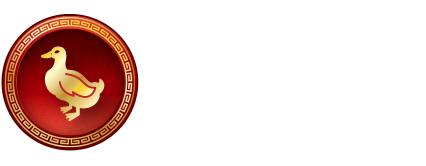

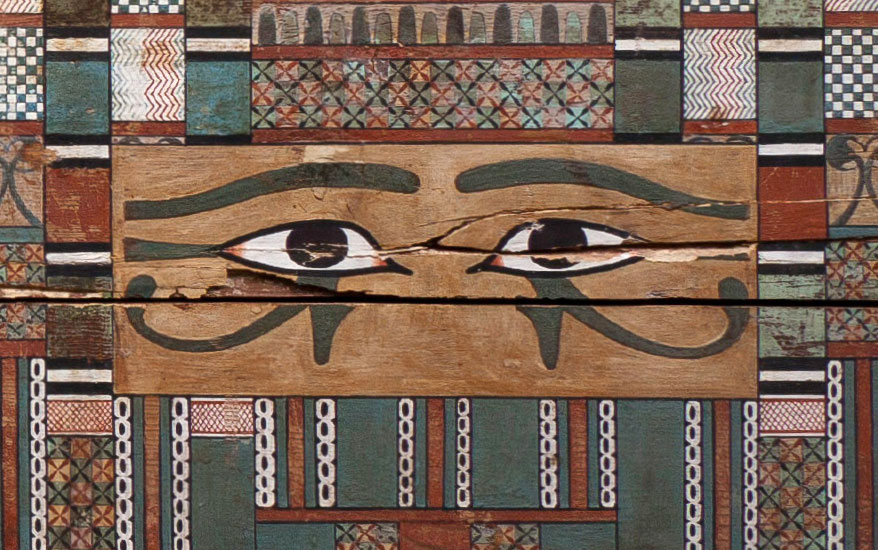

A passport for the Next World

Totenpass (plural Totenpässe) is a German term sometimes used for inscribed tablets or metal leaves found in burials primarily of those presumed to be initiated into Orphic, Dionysiac, and some ancient Egyptian and Semitic religions. The term may be understood in English as a “passport for the dead”.

Seeing Eternity

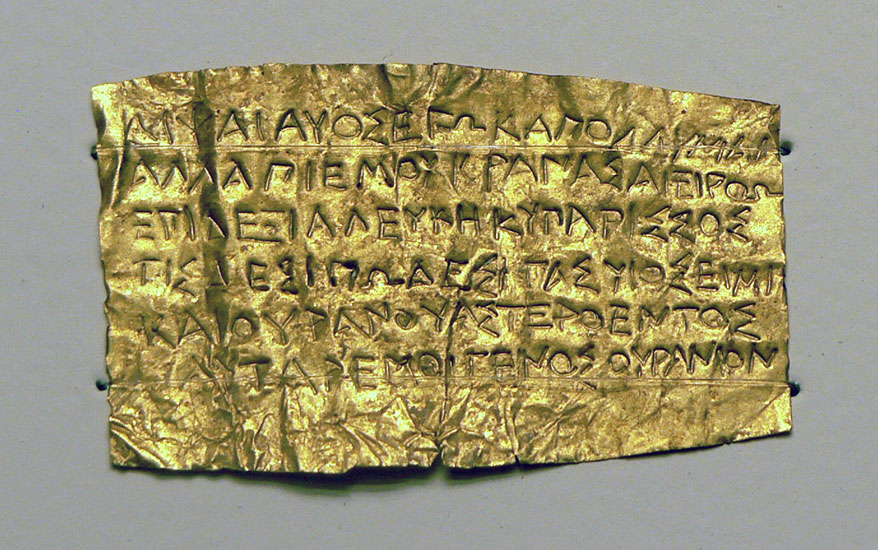

The first Egyptian coffins were produced in around 3500 BC, during the Predynastic Phase of Egyptian history, before a single king ruled the entire country; these took the form of simple uninscribed boxes, with the deceased lying in a contracted position inside. By the late Old Kingdom (2700–2170 BC), however, coffins had become rectangular, allowing the deceased to be stretched out, lying on his or her left side.

Trapping The Soul

Spirit photography (also called ghost photography) is a type of photography whose primary goal is to capture images of ghosts and other spiritual entities, especially in ghost hunting. It dates back to the late 19th century. During Victorian times it was believed that a means of trapping a person’s soul was by capturing their spirit in a photograph.

An American jewelry engraver and amateur photographer named William Mumler published, in 1862, a photograph of what was purportedly the spirit of his cousin, who had died 12 years earlier. The media sensation that this caused, led Mumler to leave engraving and to begin a successful business as a “Spirit Photographic Medium”, which he set up in New York and Boston servicing those hoping to find a supernatural connection with relatives killed in the American Civil War.5 The end of the American Civil War and the mid-19th Century Spiritualism movement contributed greatly to the popularity of spirit photography.

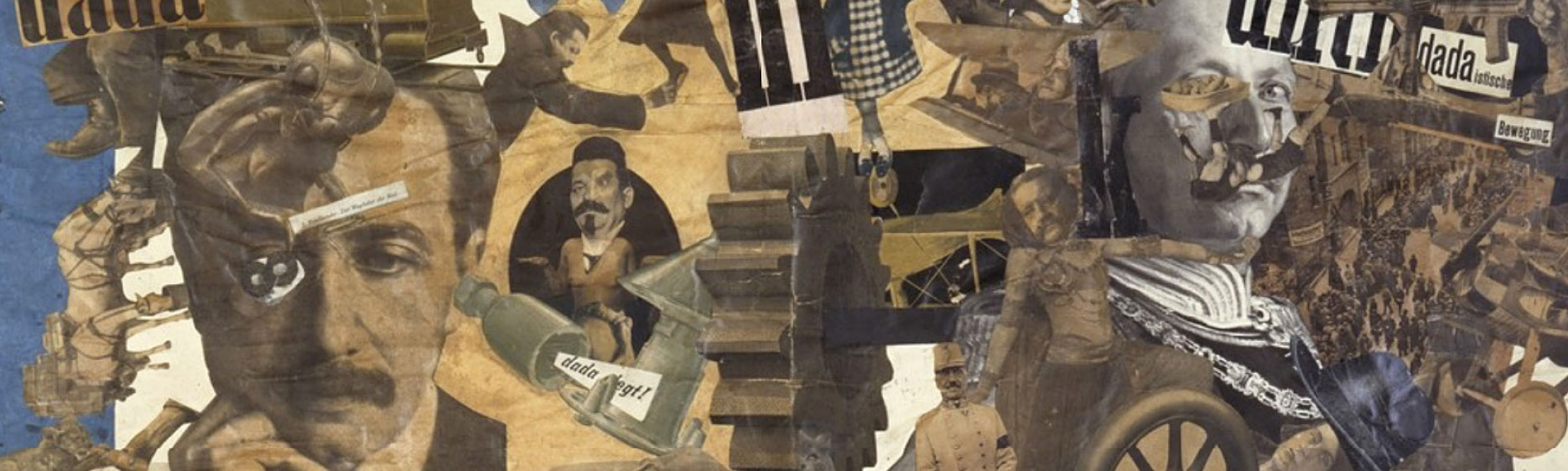

DADA and the Cut-Up technique

DADA or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century, with early centers in Zürich, Switzerland, at the Cabaret Voltaire (c. 1916). New York Dada began c. 1915, and after 1920 Dada flourished in Paris. Dadaist activities lasted until the mid-1920s. Developed in reaction to World War I, the Dada movement consisted of artists who rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society, instead of expressing nonsense, irrationality, and anti-bourgeois protest in their works. The art of the movement spanned visual, literary, and sound media, including collage, sound poetry, cut-up writing, and sculpture.

DADA artists believed that collages and montage were an extension of the eye. Dada art was a movement closely linked to emotions and fragmented concepts. In the early 1950’s artists begun to experiment again with montage techniques. During this time the cut-up technique was born.

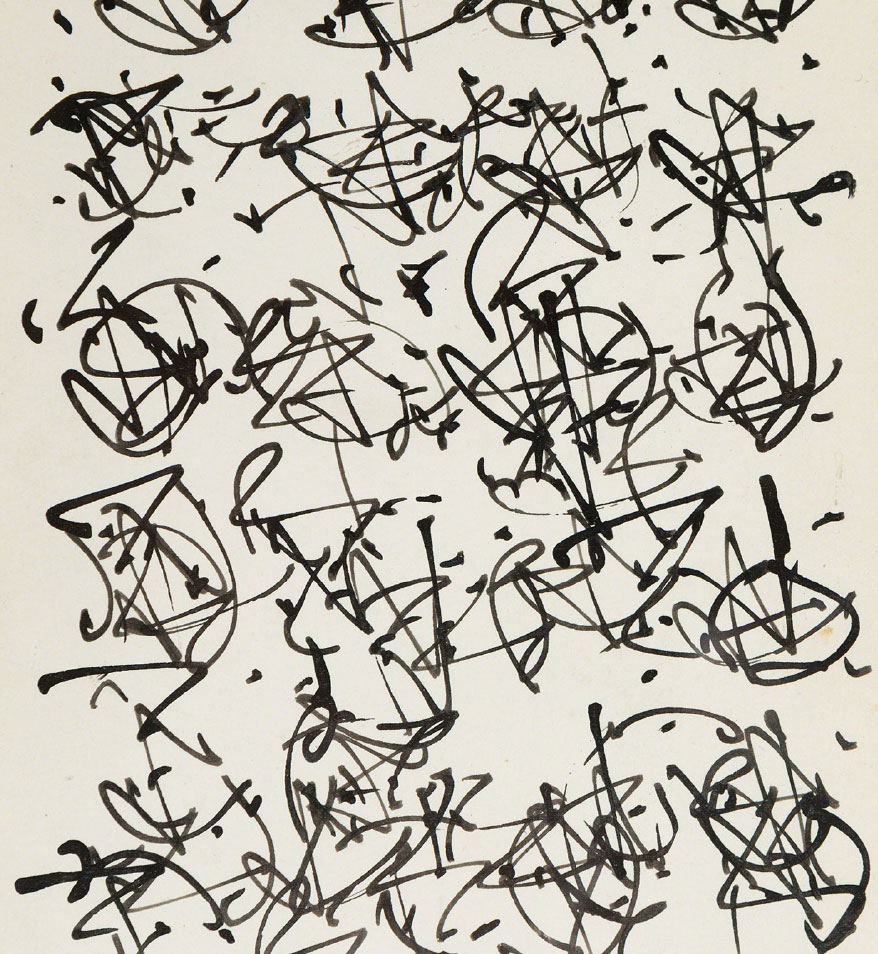

The cut-up technique (or découpé in French) is an aleatory literary technique in which a written text is cut up and rearranged to create a new text. The concept can be traced to at least the Dadaists of the 1920s, but was popularized in the late 1950s and early 1960s by painter and writer Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs.

Brion Gysin more fully developed the cut-up method after accidentally re-discovering it. He had placed layers of newspapers as a mat to protect a tabletop from being scratched while he cut papers with a razor blade. Upon cutting through the newspapers, Gysin noticed that the sliced layers offered interesting juxtapositions of text and image. He created a number of Caligrammes and paintings based on the cut-up technique.

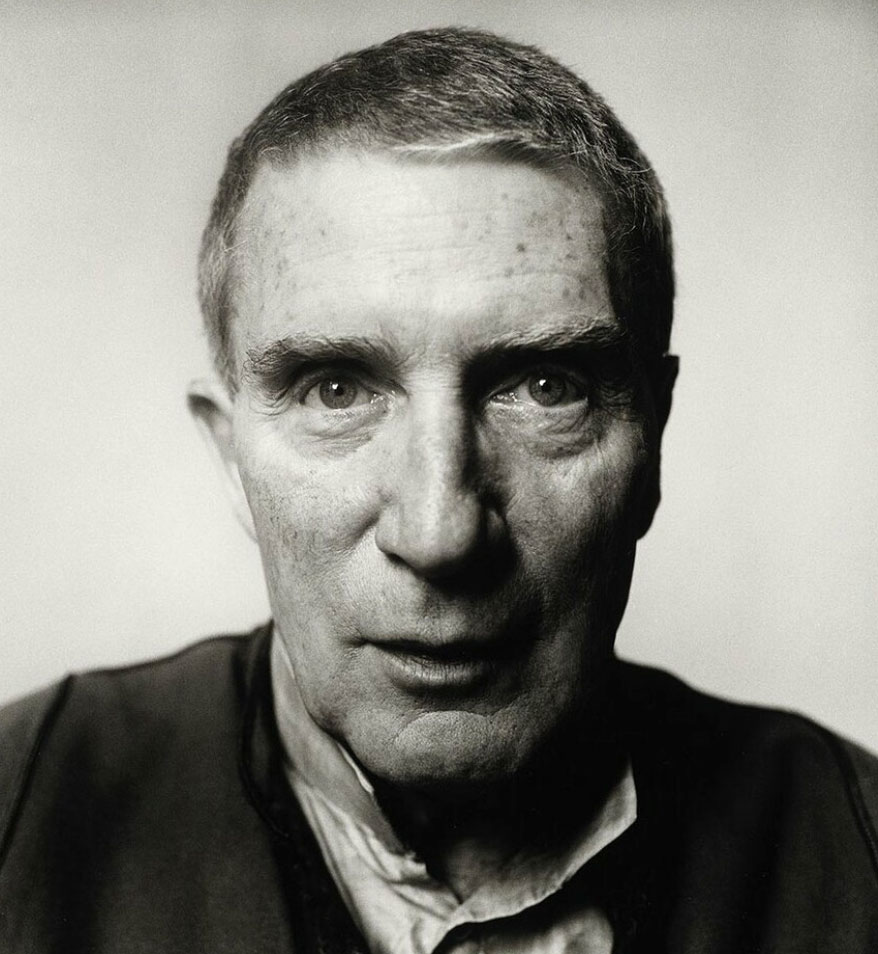

Disembodied Words: William Burroughs on Raudive and EVP

On July 20, 1976, a lecture by William S. Burroughs was conducted at Naropa University in Boulder Colorado. The lecture was taped by the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. In this lecture, Burroughs covers the cut-up method of writing in some detail, & reads from his own cut-up writings, as well as some by Burroughs’ sometime collaborator Brion Gysin. Burroughs describes how some cut-ups appear to be uncanny prognosticators, accurately predicting future events, according to Burroughs.

He also describes experiments with audio cut-ups using tape recorders. He had intended to play recordings of some of Gysin’s tape experiments at this lecture, but the tapes had not arrived on time. Instead, Burroughs describes some of the cut-up tape experiments. Burroughs’s lecture describes tape experiments that interested him conducted by paranormal investigators & what today is commonly known as EVP (Electronic Voice Phenomena), where tape recorders are supposed to record unexplained mysterious human voices though no such sound input is available to the recorder. Burroughs refers to these as “Paranormal Voices” experiments/phenomena.

The Beat Goes On: William Burroughs in México and the Beat Movement

In the throes of America’s post-World War II period, there arose a counterculture literary movement known as Beat Movement. The Beat movement, also called Beat Generation, was an American social and literary movement originating in the 1950s and centered in the bohemian artist communities of San Francisco’s North Beach, Los Angeles’ Venice West, and New York City’s Greenwich Village. Beat poets sought to transform poetry into an expression of genuine lived experience. They read their work, sometimes to the accompaniment of progressive jazz, in such Beat strongholds as the Coexistence Bagel Shop and Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights bookstore in San Francisco.

Allen Ginsberg’s Howl became the most representative poetic expression of the Beat movement: the poem itself embodied the essence of the Beats’ voice; its first performance, in 1955, was chaotic and liberally sprinkled with obscenities and frank references to sex, all intended to liberate poetry from academic preciosity. It was a disorderly celebration; and the obscenity trial, in 1957, that followed its publication showed the movement’s social and political relevance.9 But the influence of one notorious Beat has been all but forgotten: that of Joan Vollmer. Vollmer often hosted the Beats at her Upper West Side apartment in New York and participated in their wide-ranging intellectual discussions. During this time she met William Burroughs.

In 1944, both moved into an apartment they shared with Jack Kerouac and Edie Parker, Kerouac’s first wife. Burroughs and Kerouac got into trouble with the law for failing to report a murder involving Lucien Carr, who had killed David Kammerer in a confrontation over Kammerer’s incessant and unwanted advances. During this time, Burroughs began using morphine and became addicted. He eventually sold heroin in Greenwich Village to support his habit. Vollmer also became an addict, but her drug of choice was Benzedrine, an amphetamine sold over the counter at that time. Burroughs fled to Mexico to escape possible detention in Louisiana’s Angola state prison. Vollmer and their children followed him. Burroughs planned to stay in Mexico for at least five years, the length of his charge’s statute of limitations. Burroughs also attended classes at the Mexico City College in 1950, studying Spanish, as well as “Mexican picture writing” (codices) and the Mayan language with R. H. Barlow.

But their romance was cut short in 1951. On Sept. 6, 1951, Vollmer and her fugitive husband played a game that would take her life. Their life in Mexico was by all accounts an unhappy one. Without heroin and suffering from Benzedrine abuse, Burroughs began to pursue other men as his libido returned, while Vollmer, feeling abandoned, started to drink heavily and mock Burroughs openly. One night while drinking with friends at a party above the American-owned Bounty Bar in Mexico City, a drunk Burroughs allegedly took his handgun from his travel bag and told his wife, “It’s time for our William Tell act.” There is no indication that they had performed such an action previously.

Vollmer, who was also drinking heavily and undergoing amphetamine withdrawal, allegedly obliged him by putting a highball glass on her head. Burroughs shot Vollmer in the head, killing her almost immediately.

According to police records, Burroughs told authorities that he had wanted to show off his new pistol and marksmanship. The police report then stated that “Burroughs thought [Vollmer] was joking” when she collapsed after he shot at her. He was apparently too drunk to realize that he had shot her right in the forehead. The incident remains shrouded in mystery. In the ensuing years, Joan Vollmer’s death has both haunted and inspired Burroughs. As he wrote in his 1985 novel, Queer:

“I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would have never become a writer but for Joan’s death. I live with the constant threat of possession, and a constant need to escape from passion, from control. So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the ugly spirit, and maneuvered me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.”

William Burroughs

Image Credits

“Rapture”, Montage by Mauricio Reyes, 2022

Brion Gysin, © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, courtesy Pace / MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Brion Gysin, 1916–1986, Magic Mushrooms, 1961, Work on paper. October Gallery, London

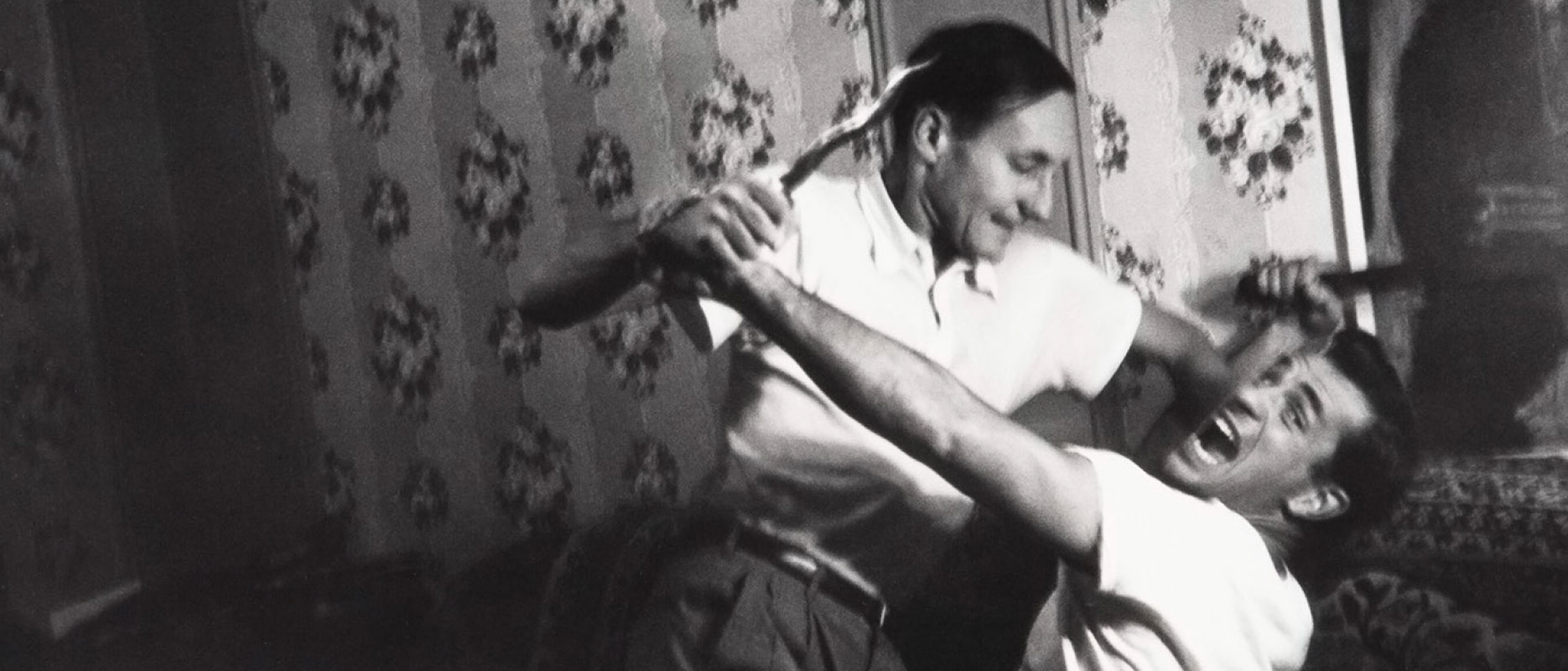

Allen Ginsberg American, 1926–1997 – William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, 1953, Gelatin silver

Burroughs at Lecumberri prison, Mexico City, 1951

Joan Vollmer, location unknown, Mexico City, 1951